I refuse to recite the Creed.

Sorry, but I’m going to be stubborn about this. I refuse to recite the Creed. I won’t recite it, won’t pledge allegiance to it, won’t swear or even affirm that I believe it. When I worship in a church that uses the creed in worship (which is more often than not), I’ll stand there politely, I won’t frown and tsk-tsk the other worshippers – but I won’t participate either. I refuse to recite the Creed. If I’m looking to join a church (my membership currently in limbo due to my sojourning lifestyle) and they insist on a commitment to the Creed as a condition of membership, then we’ll have to part ways. I won’t do it.

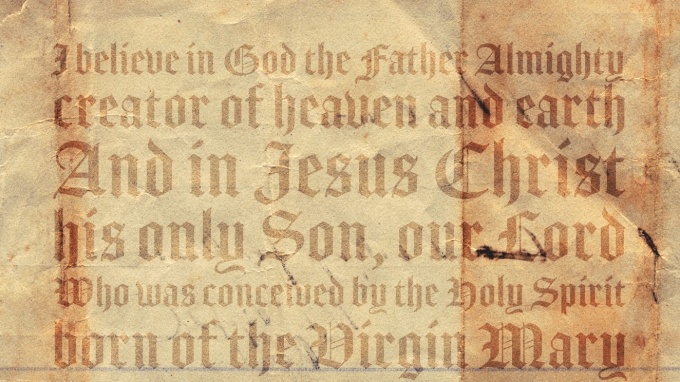

And it matters not which creed we’re talking about. Most creedal churches seem to use the Apostles Creed, but I don’t really care if it’s the Apostle’s Creed, the Nicene Creed, the Westminster Confession, the 95 Theses or the preacher’s laundry list. I won’t be bowing down to worship in front of it. Creeds are destructive of Christian fellowship, and more importantly, they’re bad theology. I don’t mean that they contain bad theology – the theology in them might be perfectly fine, or might not – but the point is that the idea of the Creed itself, as a test of fellowship and summary of “the faith,” is bad theology.

The tradition I grew up in, the church that ordained me into the ministry, is the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), part of the Stone-Campbell movement that also includes the Churches of Christ and independent Christian churches. The three estranged branches agree on little, but all three have remained faithful to Alexander Campbell’s rejection of creeds in the church. I remain faithful to this conviction as well, not as a matter of tradition or denominational pride (“denominationalism” is a sin in the Stone-Campbell churches), but because Campbell’s reasons for rejecting the creed were sound.

In Campbell’s day (early 19th Century), the Presbyterian church he was originally part of was divided by numerous schisms, and creeds became a way of distinguishing which group you were in, marked you as inside or outside “our” church. Creeds have in fact always functioned that way since early catholic Christianity, drawing a line around orthodox (“correct”) teaching and excluding heresy (“wrong teaching”). Anyone not willing to affirm the creed had marked themselves as a heretic to be excluded from fellowship. In Campbell’s day, you had to affirm the local church’s version of the Westminster Confession to get a token which you could present to receive communion. One day Campbell walked to the front of the church in worship, tossed his token onto the table, turned his back and walked out never to return (fond of drama was Mr. Campbell). And in the churches he founded, which became the Restoration movement, the slogan became “no creed but Christ” – no test of fellowship other than faith in Jesus Christ. So this first objection to the creed seems to me a sound one: it is an unnecessary barrier to fellowship with other disciples of the one Master.

But there is a much more important problem with the creed, and that can be seen in the introduction to the recitation of the creed in worship: “Let us say what we believe . . .” This is a theological error, and a serious one. The issue is the proper object of faith. In what, precisely, does the Christian believe? The very existence of the creed – any creed – contends that Christian faith is the affirmation of certain ideas: one God the creator, Jesus fully human and fully divine, virgin birth, worldwide church, predestination (or not), whatever. It makes no difference what ideas you throw in here, the whole business is wrong-headed. The proper object of faith is not an idea (doctrine), nor is it a book (the Bible). The proper object of faith is a person. Christian faith is faith in Jesus Christ. Faith is not assent to any idea, however noble, but personal trust and commitment to the person of Jesus Christ. To be a Christian is not to believe a set of ideas but to trust your life to a person, to the God revealed in the face of Jesus Christ.

One cannot overstate the importance of this distinction. How many people won’t listen to the Gospel because they refuse to accept certain doctrines and teachings “on faith”? How often have various doctrines or historical claims been stumbling blocks, and unnecessary ones, to people coming to faith? On the other hand how many people continue to cling to doctrines and historical claims that don’t make any sense, on the assumption that we know these things, and “have to” believe them, “by faith”? The truth is that we don’t know anything by faith. Faith is not a way of knowing things. Knowledge is a human endeavor, and it’s carried out by the usual human tools: think, study, explore, listen, consider alternatives, weigh the evidence, come up with what makes the most sense. Faith is about none of this. Faith is about the fundamental trust that my life depends upon God, that I belong body and soul (or, with all that I am) to the God revealed in Jesus Christ. That is faith. Everything else is an afterthought. Neither the Bible nor theology are proper objects of faith. Not to diminish either one, they’re simply not the proper objects of faith.

Theology is, to use a classic expression, the “languaging of faith,” putting our faith into human language that we can communicate to others and with which we can reflect on the significance of faith in our lives. It all starts with faith, this personal delivering of oneself to Jesus Christ. Theology comes later, as we try to make sense of our lives in light of faith. Theology, then, is a human endeavor, subject to all the frailties and errors of human judgment. Every attempt to claim otherwise, to make some theology “sacred,” “divinely inspired,” “infallible” is horse hocky at best and idolatry at its worst.

The Bible, on the other hand, is our witness and testimony to Christ. It is, as Luther said, “the cradle that holds the Christ child.” You’re looking for Christ? Where you going find him? With the preacher on TV? In your “heart” (just as likely your imagination)? The Bible is where we look to find Christ, it’s the witness and testimony that bridges the centuries so we can know the Master ourselves. Strange then that so many insist on worshipping the cradle rather than the Christ child. We don’t take the Bible “on faith,” as if salvation was promised to “whosoever believeth in this book” (I’m pretty sure it says “whosoever believeth in him”). Faith, then, is not in a book, not in an idea or a doctrine, not in a miracle story whether in past or future. Faith is in Jesus Christ – or it’s not Christian faith at all.

An old sermon illustration I’m quite fond of: you come across a man working on a boat on the shore of a river. He asks you,”Do you believe this boat will navigate this river?” You say, “Sure, it looks like it will.” “Great,” he says, “hop in.” Faith is not about the first question but the second. The issue is not your knowledge or opinions about boats and rivers, but whether you’re going to get into the boat. Now, accurate knowledge of boats and rivers would certainly come in handy once you’re in that boat on the river — theology has its place — but better a misinformed or misguided person who actually got into the boat than someone who just talks about boats and never gets in.

So let’s be clear in our preaching and our worship about where our loyalty lies, about where our faith dwells, to what we would invite others as we preach the Gospel. We preach not a system of ideas, not an orthodoxy, not an institution, but a person Jesus Christ. So if you are a pastor or worship leader, consider dispensing with the Creed in worship and practice. As for me, while the Creed is recited around me, I’ll quietly recite to myself the New Testament confession: “Jesus is Lord, Jesus is Lord, Jesus is Lord . . .”

Mark Plunkett

Columbus, GA Feb 2016